Gender inequality is still a big issue. Yet overall, Western society has made some significant strides in the last century or two, especially in the last few decades. So in honor of Women’s History Month, we’re highlighting some of the progress we’ve made in the hopes of inspiring ongoing change.

The theme for this year’s Women’s History Month (March of 2022) is "Women Providing Healing, Promoting Hope." So we’re taking a look at women’s progress in several areas, starting, fittingly, with Healthcare. Later in the month we’ll also dive into women’s progress in the areas of Sports, and Money.

Women in Healthcare: Then and Now

Records of early civilizations, including ancient Egypt and Greece, indicate that women commonly practiced medicine. Both Isis (the Egyptian Goddess of Medicine) and Hera (Chief healing deity in Ancient Greece) are female. There are women documented as medical school students, midwives, and surgeons as early as 5500 years ago.

But the history of women in healthcare has not followed a steady upward slant. It’s been more of a meandering path with some extreme dips. Fortunately, there’s also been a notable uptick of women in healthcare in modern Western culture beginning since the 1970s.

The women’s movement in the 1960s and 1970s changed both attitudes and laws in the US.Title IX of the Higher Education Act of 1972 banned discrimination on the grounds of gender. In addition, medical colleges rallied for equal rights in the healthcare professions.

In the 40 years between 1930 and 1970 just 14,000 women graduated from medical school. By contrast, in the 10 years between 1970 and 1980, more than 20,000 women graduated from medical school, according to Wikipedia.

With more women in healthcare and medicine, the practice itself changed, especially concerning women’s health. Among other things, women (and patients more generally) were encouraged to embrace a more active role in their own health. There was also greater focus on the health of women and families.

An example of more DIY-style healthcare is the widely distributed book from 1970, “Our Bodies Ourselves.” The book served as a rallying cry and manual for women to take better charge of their own bodies.

Women in the Healthcare Industry Today

A lot has changed. For one thing, in the US, the majority of medical school students are now women, according to the Association of Medical Colleges. In addition, women hold more than 75% of healthcare jobs in the US. These jobs are most likely to be in caregiving as opposed to diagnosis (for example, more nursing aides, fewer doctors).

Despite the prevalence of women in healthcare, women are less likely than men to hold leadership roles. Women lead just 19% of hospitals. And, in the healthcare industry overall, women make up only 13% of CEO roles and 33% of senior leadership positions.

Even when men and women hold the same types of healthcare jobs, they don't get equal pay. For example, in 2018, female surgeons made $0.67 to every $1 earned by their male counterparts, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In addition, professional challenges include sexual harassment and violence against women. Women of color also face a lack of racial equity, and the challenges facing women and minorities can compound each other.

On the plus side, women's employment at all levels in healthcare shows greater gender equality than in corporate America overall. (I’m not totally sure that qualifies as good news, but still.)

In addition, a report by LeanIn.org and McKinsey found that women in healthcare jobs are more satisfied in their careers than their male counterparts, from entry levels to the C-suite.

Some Notable Women in Healthcare History

While there are many notable women in Western healthcare history, there are a few who have become household names. Among them are Clara Barton, Elizabeth Blackwell, and Florence Nightingale, from about 150 years ago, and Sarah Gilbert, who played a key role in developing the Oxford—AstraZeneca COVID vaccine in 2020.

Clara Barton, Humanitarian Visionary – Clara founded the American Red Cross in 1881 at the age of 59, and proceeded to lead it for the next 23 years. Known as the “Angel of the Battlefield,” Clara risked her life to bring supplies to wounded soldiers in the field as a self-taught nurse during the Civil War.

Clara is considered a visionary leader whose humanitarian work included supporting people around the world in need during disasters, helping the homeless and poor, and developing first aid kits.

Elizabeth Blackwell, First Female Doctor & Pioneer in Education – Elizabeth, who was born in Britain, overcame significant gender bias and prejudice to become the first woman to earn a medical degree in the United States. After she had been rejected by several other medical schools, the male students of Geneva Medical College in New York voted unanimously to accept her “unusual” application. She graduated first in her class and went on to have a wide influence in the UK and the US.

Elizabeth opened an infirmary with the goal of employing other female doctors, and later established a medical college for women. She was also the first woman to publish a medical paper, which was highly empathetic toward patients. Her empathy and focus on the patient was considered a “feminine” trait.

Florence Nightingale, Healthcare Reformer & Founder of Modern Nursing – Florence, known as the “Lady with the Lamp,” was born in Florence, Italy, to wealthy British parents. Against her parents’ wishes, she refused to marry a “suitable” gentleman and instead enrolled in nursing school in Germany in 1844.

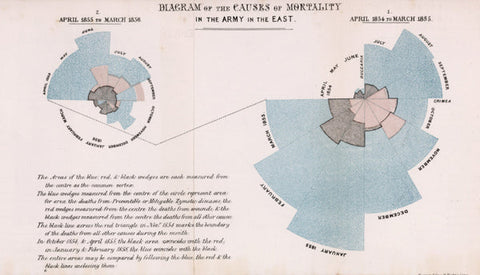

It was in the Crimean War of 1853 (the British Empire vs. the Ottoman Empire) that Florence made her mark, transforming the standard for hospital and care facilities. She pushed for the inclusion of female nurses on the front lines and radically revamped sanitation practices such that mortality rates dropped by two thirds.

Later in her career, Florence analyzed data on the British army to show that 16,000 of 18,000 army deaths were from preventable diseases, not battle. She was able to translate the data visually in a way that regular citizens could understand and use. Below, the blue areas of the "Nightingale Rose" diagram represent preventable mortalities, while pink represents mortalities from wounds, and black represents all other causes of mortality.

Sarah Gilbert, COVID Vaccine Developer – Dame Sarah Gilbert is a British vaccine specialist and a professor at Oxford University in the UK. Her background includes the development and testing of a universal flu vaccine.

On the first day of 2020 Sarah read an article about an unusual disease outbreak in Wuhan, China, which would later be called COVID-19. Within two weeks, Oxford had developed a vaccine. The vaccine she helped to develop became available to the public within the year, dramatically reducing deaths from the pandemic.

Promoting Women’s Progress in Healthcare

Promoting women’s progress in healthcare relies on a combination of cultural and workforce factors. Unfortunately, women and girls have been set back professionally by the COVID-19 pandemic, forcing many out of work and/or into taking on increased family responsibilities.

The women in healthcare report by Lean In and McKinsey suggests several ways organizations can support and advance women in healthcare, including:

- Ensuring that promotions, evaluations, and external hiring processes are fair

- Investing in cultural training to promote a more diverse and inclusive workforce

- Creating flexibility in the workplace, making it easier to combine family with full time or part time work

It’s pretty clear that support for both men and women in caring for their families is a critical factor in their potential for career success. Vaccine developer Sarah Gilbert said in an interview:

“Work life balance is very difficult, and impossible to manage unless you have good support. Because I had triplets, nursery fees would have cost more than my entire income as a postdoctoral scientist, so my partner has had to sacrifice his own career in order to look after our children.”

Sarah’s children are now grown, but the challenge for many of juggling career and family remains. Most often women are the partners who are more willing, able, or expected by societal standards to “sacrifice their own careers” to perform unpaid work compared to men. How do you think we should address the challenge of supporting women and their families, and how much has it shaped your own professional trajectory?